Example Projects

The Washington Forest Collaborative Network is engaged in a diverse set of projects to increase the pace and scale of forest restoration while contributing to local economies. Click on each of the tabs below to learn about some of the Network’s successes.

Darrington Forest Collaborative

Stegelsen Stewardship Project

Segelsen stewardship is the first pilot project of the Darrington Collaborative on the Darrington Ranger District of the Mount Baker Snoqualmie National Forest (MBS). The Stewardship project has two components: a thinning project in the Segelsen area and aquatic restoration projects associated with the Clear Creek Road.

The overall goal of this pilot project is to try different prescription approaches to build group understanding and learning regarding different management approaches that could be applied more broadly across the Darrington Ranger District.

Below are the main objectives:

Ecological

1. Use variable density thinning to accelerate the development of old-forest characteristics and functions, including large trees with complex crowns, a multistory canopy, snags and downed logs, a diverse plant community, and a patchy, variable structure that includes openings.

2. Minimize damage and disturbance to riparian areas and soils related to road conditions moving forward.

Social and Economic

1. Provide work for local logging contractors and wood volume for local wood processing industries.

2. Provide revenue for aquatic restoration projects, including the Clear Creek upgrades.

3. Develop common understanding of forest management approaches and their effects among collaborative members. Test different prescription and contracting approaches that have ecological benefits and can be replicated on larger projects.

“The Darrington Collaborative has been a unique and rewarding experience for the community of Darrington to build trust with industry, environmentalists and local leaders to provide economic benefits to our community through sustainable logging, forest restoration and STEM education.”

– Dan Rankin, owner of Dan Rankin Milling and lifelong Darrington resident

The Segelsen Stewardship Project involved efforts by staff at the Mt. Baker Snoqualmie National Forest and members of the Darrington Collaborative including representatives from Washington Wild, Atterbury Consultants, American Whitewater, Glacier Peak Institute, The Wilderness Society, Darrington Mayor and local mill owner Dan Rankin, Pew Trusts, local contract logger Steve Skaglund, STEM educator Mike Town and retired local logger Bob Boyd.

In October 2017, Hampton Lumber secured the winning bid for the Segelsen stewardship sale. Hampton offered a strong bid well over the minimum acceptable offer at $358,000, or $29.14 per ton. The unit will be harvested and the Clear Creek Road aquatic restoration work will be completed in the summer of 2018.

Next up, the Darrington Collaborative is working with the Mt. Baker Snoqualmie National Forest to identify multiple thinning restoration projects in FY 18 and FY 19 as well as planning for a longer-term landscape level environmental assessment in the Darrington area.

South Gifford Pinchot Collaborative

Temporary Roads Monitoring Pilot Project

The overarching goal of this project is to explore how monitoring may be used to increase efficiency and trust so that more restoration work is accomplished on the ground. The group selected temporary roads for a pilot project because this is a controversial topic that generates many comments during the NEPA process. Currently, there is a lack of knowledge on how temporary roads recover after obliteration. While implementation monitoring is completed during timber sale contracts, the Mt. Adams Ranger District does not monitor temporary road restoration. This project evaluates road restoration and recovery by monitoring the effectiveness of specifications in decompacting soils, preventing erosion, and establishing productive soils and revegetation.

“Pulling people together and actively engaging them in science not only builds trust in one another, but also in the scientific process. It helps connect values with data.”

–Sharon Frazey, Mt. Adams Resource Stewards

The South Gifford Pinchot Collaborative group initiated this project with support from the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, and coordination and technical assistance provided by Mt. Adams Resource Stewards and Cascade Forest Conservancy, two collaborative member organizations. Funding is provided through a National Forest Foundation Community Capacity Land Stewardship Program grant.

Through this monitoring pilot project, the collaborative intends to increase shared understanding of temporary road restoration effectiveness and monitoring techniques, build capacity for agreement, and enhance volunteer engagement. In the fall of 2018, the group tested out the monitoring protocol and plans to implement the pilot project in the 2019 field season. The collaborative will also be working this winter on a long-term monitoring plan that assesses past vegetation projects and economic effects of stewardship sales.

Photo: In October 2018, collaborative volunteers collected data on vegetation cover at a former temporary road site.

Photo credit: Sharon Frazey

Chumstick Wildfire Stewardship Coalition

Watching Wildfires at the Wenatchee River Salmon Festival

By Corrine Hoffman, CWSC Director

This year, the Chumstick Wildfire Stewardship Coalition was invited to present a wildfire demonstration at the 2018 Wenatchee River Salmon Festival. Working with Festival staff and stakeholders, CWSC created a program for the event called ‘Watching Wildfires.’ 3rd through 5th grade children from Chelan County School District attended the Festival’s educational events over three days, expanding their horizons on subjects from landscape and wildlife ecology to cultural and art exhibitions.

The CWSC’s presentation attempted to answer the questions: ‘how do the conditions that make healthy fire possible differ from those that create catastrophic wildfires?’ and ‘how does fire affect our dry forest ecosystem at the landscape level?’ The introduction to the presentation included dry forest conditions and how management over the years has changed the landscape. We went on to investigate how those fire types change the ecosystem at a landscape scale, discussing soil destruction and erosion issues, and finally runoff in waterways affecting aquatic life.

Photo: CWSC is re-creating a catastrophic wildfire on a model mountain, showing the result of high fuel loads. Corrine Hoffman, CWSC Director, left, Mike Smith, Chelan County Fire District 3 Fire Fighter, right.

The Chumstick Wildfire Stewardship Coalition’s presentation included a ‘forest fire’ to ‘flooding’ demonstration, linking ecosystems at their landscape level connections with a hands-on focus. At the three day Festival, the CWSC was able to teach approximately 360 children and 100 adults about these ecosystem concepts – starting with the forests of yesterday and moving to the overcrowded, unhealthy forest conditions we tend to see in forests today. The Coalition talked about low-intensity fires and catastrophic wildfires, and students heard why forest composition and thus fire behavior has changed over the years.

Photo: After the fire erosion demonstration: these boys are creating a ‘rain shower,’ flushing ash and debris down our model mountain after a catastrophic wildfire. Corrine Hoffman, CWSC Director, shown guiding activity on left.

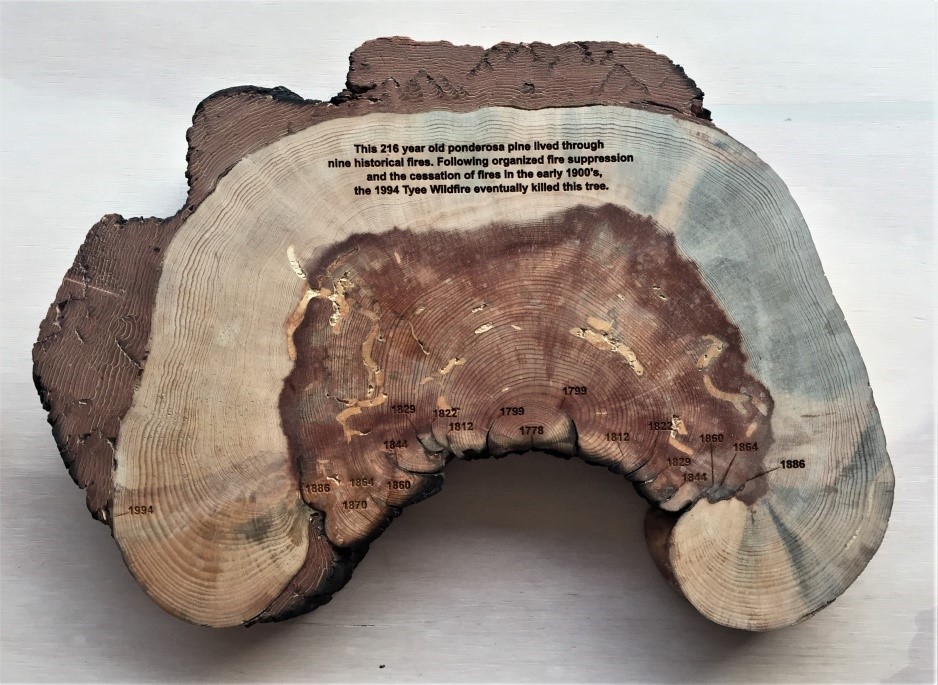

During the three day Festival we demonstrated the effects of different types of forest management on our dry forest environment. The removal of fuels from the dry forest system was historically – and naturally – accomplished by low intensity fires that burned through the forest, eating fuels in the form of debris and vegetation as it went. When these ‘forest-cleaning’ fires were stopped in the early 1900’s, forest fuels started to accumulate- and they no longer had low-intensity natural fires to remove fuels. Forests began to be filled with vegetative fuels such as trees, shrubs, herbs, and debris. This build-up changed the composition of the forest, leaving it vulnerable to bigger, hotter fires.

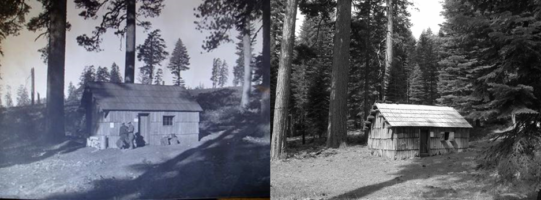

Photo: Bear Creek Station in Pumas National Forest, left circa 1915, right circa 2002. The natural fire regime with historical forest conditions are shown on the left and the overstocked current forest conditions are shown on the right.

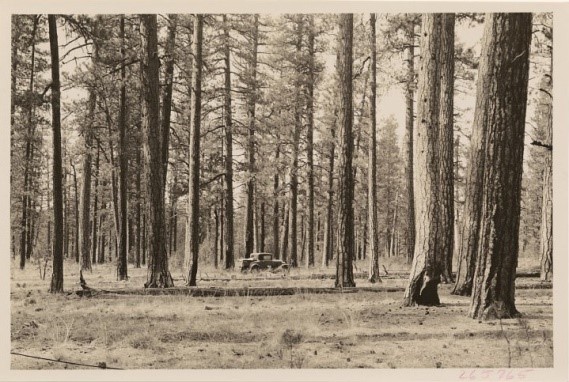

In order to tell our forest’s story effectively, we went back over a hundred years to the time before fire suppression here in the western United States. Historically, dry forests were open full of well adapted species such as towering Ponderosa Pines that settlers were able to drive wagons through with ease. These ecosystems were supremely fire-adapted, with trees that actually needed low-intensity fires just to let their cones open so they can reproduce. We discussed the logging of those giant trees, and how fire and that fire’s repression for over 100 years affected our forests and now affects us every year in fire season.

Photo: Picture circa 1931, Ponderosas, historic condition of dry forest. Note the tiny car centered in the photo.

Photo: Ponderosa Pine wood round, killed in the catastrophic 1994 Tyee Wildfire, Entiat River Valley, Washington. Note nine major wildfires in first 108 years, as marked on round, then no major wildfires for the next 108 years due to human-influenced fire exclusion.

Our region is dealing with giant wildfires of unprecedented size yearly. Smoke fills our air in the summertime, making enjoying the outdoors hazardous – even if you don’t happen to be near a fire. However, management activities are being undertaken by landowners and organizations like the Chumstick Wildfire Stewardship Coalition, along with local, State, and Federal partners, in an attempt to balance past actions through reducing the fuels that fire needs to grow. Both the United States Forest Service and the Washington State Department of Natural Resources have mandates to work together with stakeholders to restore our forests, and to protect our resources, wildlife, and communities. We are entering a new era of forest management- no longer are we managing for timber outputs alone, but working together to reduce wildfires on the land for the good of all.